- Open Source CEO by Bill Kerr

- Posts

- Unlocking Engineering Intelligence

Unlocking Engineering Intelligence

An interview with Anish Dhar, Co-Founder & CEO at Cortex. 🌵

👋 Howdy to the 1,989 new legends who joined this week! You are now part of a 208,838 strong tribe outperforming the competition together.

LATEST POSTS 📚

If you’re new, not yet a subscriber, or just plain missed it, here are some of our recent editions.

🔮 When Science Fiction Becomes Science Fact. The future is here, just like how your favorite science fiction author predicted.

🔬 The $55M Material Design Seed Round. An interview with Joseph Krause, Co-Founder and CEO, Radical AI.

💥 Strategism: The AI Revenue Per Employee War. How companies are getting leaner, and how you can too.

PARTNERS 💫

Knowledge gaps = security gaps, so let Vanta handle it.

We surveyed 3,500 business and IT leaders across the globe. One big change? They’re falling behind AI risks—and spending way more time and energy proving trust than building it.

See how your team stacks up—read the full report here.

Interested in sponsoring these emails? See our partnership options here.

HOUSEKEEPING 📨

I’m in Mexico City for the second (or third) time at the moment. What a wonderful city. The food is great, it feels super safe—although it’s kinda not—and it’s incredibly close to the U.S. if you need to duck in and out, which I do next month.

The surprising thing I have found is that there are quite a lot of networking opportunities here. I’ve visited the same cafe a couple of days in a row, struck up a conversation with an ex-Anduril product lead, and then with a RevOps manager from PostHog. |  |

By the way, if you are wondering what the image I chose for this section represents, that’s a small serving of ‘chapulines’ (grasshoppers). They are quite delicious and packed with protein. Anywho, enjoy today’s piece!

INTERVIEW 🎙️

Anish Dhar, Co-Founder & CEO at Cortex

Anish Dhar is the Co-Founder and CEO of Cortex, a San Francisco-based internal developer portal company founded in 2019. Raised in the Bay Area with a software engineer father, his passion for tech began early; he even hacked his Wii console as a kid. Before starting Cortex, Anish spent nearly five years as an engineer at Uber, joining right out of college and working on projects like Uber Eats. Experiencing Uber’s messy microservices architecture firsthand inspired him to build a solution for engineering teams struggling with service complexity and tribal knowledge.

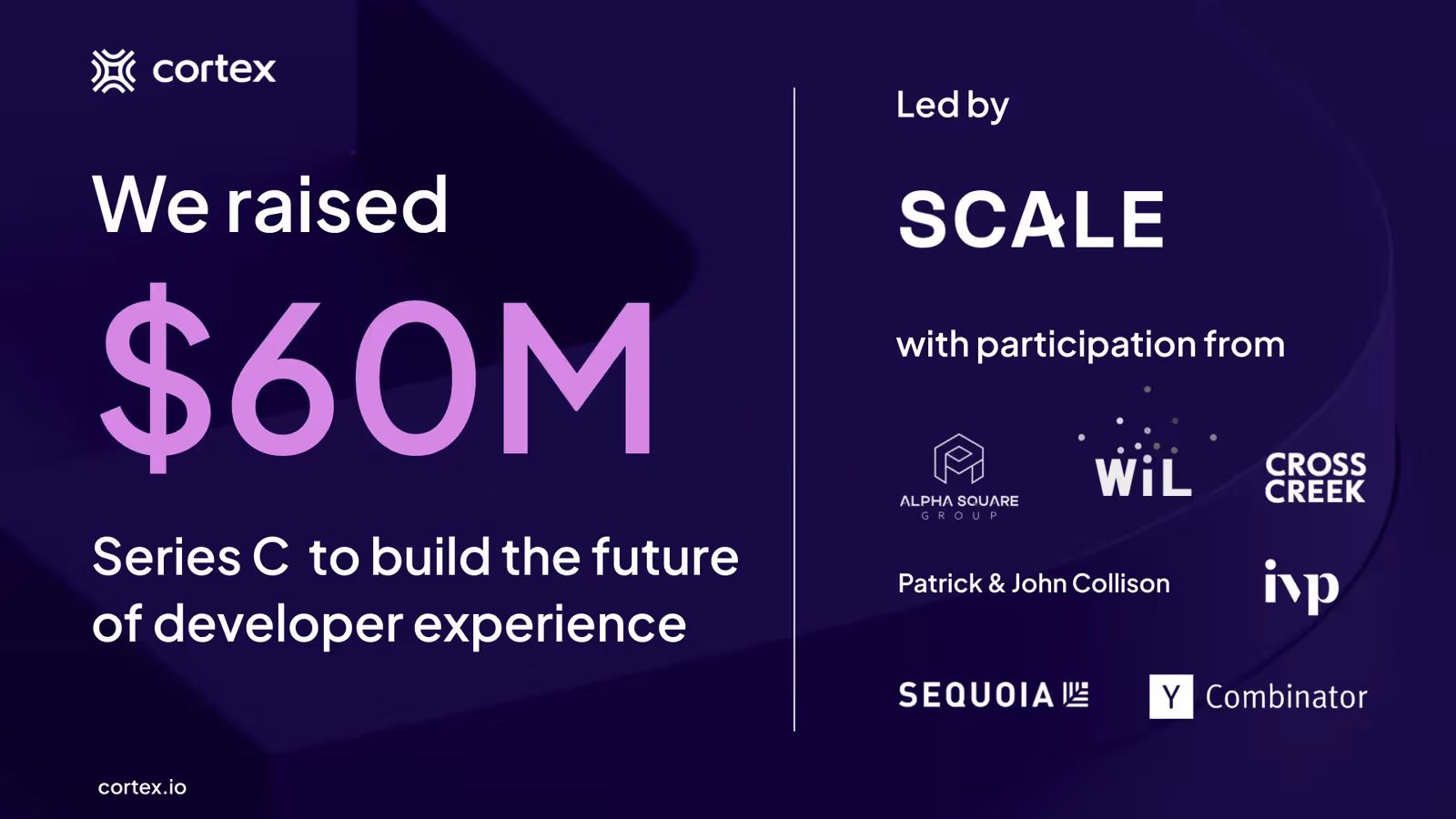

Cortex joined Y Combinator’s Winter 2020 batch and has since grown to around 100 employees. The company recently closed a $60 million Series C led by Scale Venture Partners, valuing it at $470 million. Previous backers include Sequoia, IVP, and YC, with angel investors like Stripe’s Patrick and John Collison. Anish’s long-term vision is to make Cortex the system of record for engineering teams—what Salesforce is for sales and ServiceNow is for IT.

The man Anish.

Tell us the problem you're trying to solve, and why this?

A good way to explain the problem we're trying to solve with Cortex is to share my own experiences working as an engineer at Uber, where I spent a few years working on different products. Uber is the classic case of microservices gone wrong. Over my time as an engineer there, the number of services exploded from around a hundred on just my team to over 3,000.

This was a similar story in most other parts of the company. Engineers would create services and name them after TV shows, then they would leave the company and things would break. Often the longest amount of time dealing with an incident was just trying to figure out basic context: who owned the service, where the documentation lived, whether this service met our production readiness standards, and where our production readiness standards even were. A lot of these questions just lived in people's heads or were scattered across multiple different spreadsheets.

I remember switching teams once at Uber, and this new team had built an exact duplicate service that my previous team had already built. This duplication would have saved them two weeks of work, but it happened simply because there was no internal catalog of services and context about what each service did.

Uber is obviously on one end of the service complexity scale, but I was talking with two close friends of mine—one working at a startup with just a hundred engineers and the other working at Twilio. Three very different company sizes between the three of us, but everyone had the same challenges around service complexity, service ownership, tracking and understanding quality, and tribal knowledge being rampant across the engineering organization.

That's really where the idea for Cortex came about: building this internal developer portal that drives standards, provides a consistent developer experience, and ultimately catalogs your entire software ecosystem.

What was the most difficult thing going from zero to one?

I had worked as an engineer my entire career before Cortex, so I'd never sold anything. Neither had my co-founders. It's something I've gained a ton of respect for—the art of selling and the art of even just talking about the product you're building. It took a lot of iteration to figure out how to tell the right story and how to reach out to the right person. That was one aspect of the zero-to-one journey that was very difficult.

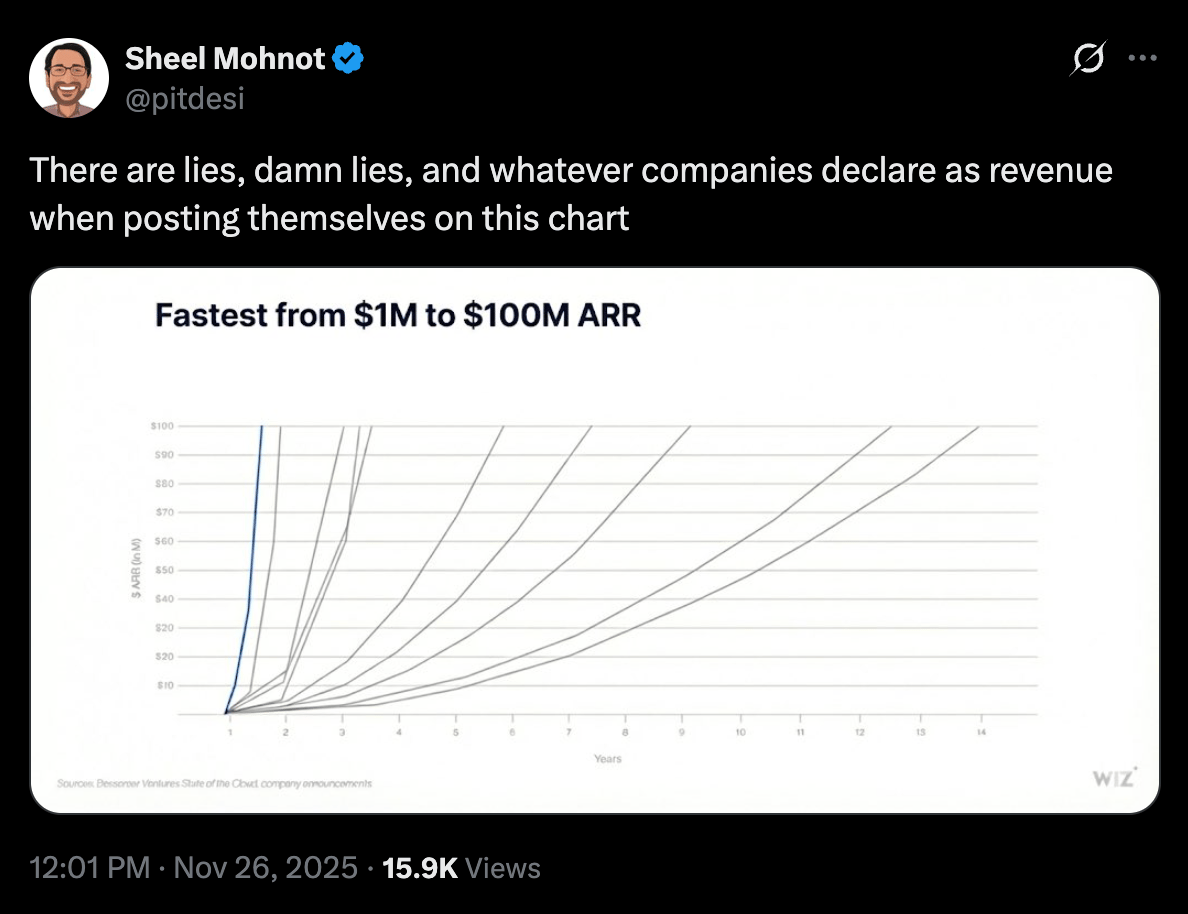

But the other aspect was that this was an entirely new category of developer tooling. There was no incumbent doing what we're doing and no existing budget that had already been allocated for something like Cortex. So not only did we have to figure out how to sell the product, we were selling something that engineering leaders had never bought before, which in the early days of a market is enormously difficult. With budgets shrinking in many cases, justification for new tools becomes very difficult. |

We really had to hone in on what the exact problem we're solving is and why this is worth creating a new budget for.

Early on, which channels worked and which didn’t?

I was the company's SDR, so I spent a lot of my day just trying to figure out how to reach the right people at the right time. Honestly, email was the thing that was most effective for us. We tried a lot of different techniques to get in front of the right people. I would look at people who were really active in certain open source projects because there was a good correlation sometimes between the types of problems that people in certain open source projects were trying to solve and Cortex. I got a few early users that way.

I also spent a ton of time really figuring out the story. I think that's actually my biggest advice to founders in the early stages: you have to really distill the product into a story that resonates with some sort of target buyer.

In our case, when we started Cortex, we would really try to sell it to developers because we thought developers would be interested in having a catalog, because we were developers. I thought, "Okay, a developer wants a catalog because when something breaks, they have all this information here." But to be honest with you, we would get a bunch of meetings because people were interested, but then no one would actually pay for it. That was an important learning for us, which was that the data is interesting and useful, but it's actually what you do with the data that can drive business value.

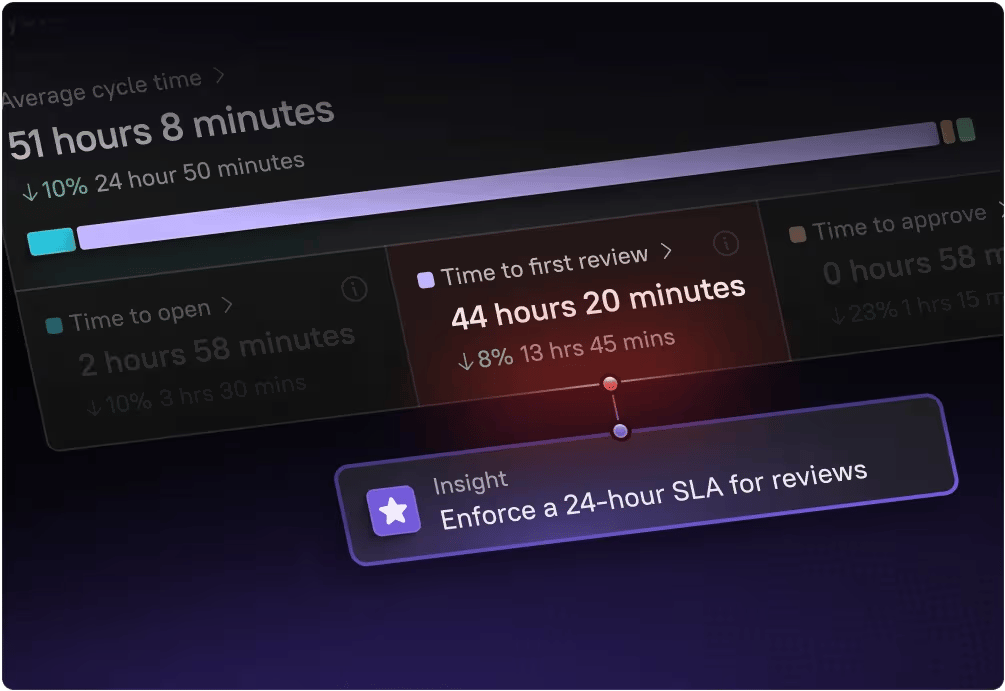

Source: Cortex.

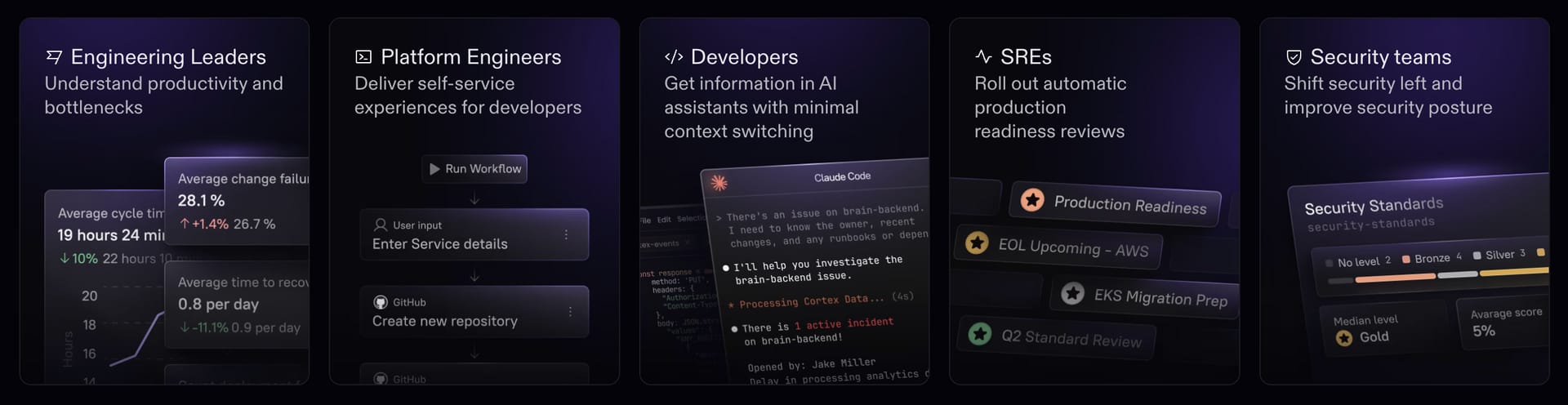

So we shifted our story to focus on SRE and platform engineers. We pivoted the story around, not just cataloging your services, but once you have this data inside the catalog, you can start automating things like production readiness or a security audit. For SREs, they were often tracking this in spreadsheets—a horribly manual process that was very ineffective because you couldn't show the results to the CTO.

Ultimately, that was a compelling enough narrative and story where not only were we able to get interested meetings, but it converted our first sale as well. I think that gave us repeatability and confidence that we should keep doubling down on it.

How has your early storytelling and sales evolved into your go-to-market today?

I think it's the most important part of my job today as a founder and CEO—I'm constantly telling stories internally to align the company and externally, whether it's about our product roadmap to customers.

The product vision has evolved a ton. When we started the company, it was just a microservice catalog specifically focused on microservices. But then we noticed that customers were tracking APIs and third-party vendors, and all these different types of components that go into their software. We realized that it's not just about your microservices. Actually, software has just become so complex. You have all your cloud infrastructure, and by the time you get to 50 engineers, there are so many components that go into your software that it's more than just a microservice catalog.

That evolved our thinking into: well, Cortex can be the first system of record for engineering in the same way sales has Salesforce and IT has ServiceNow. Engineering has historically relied on JIRA and Confluence and Google Docs to store all this information, but they're not built for engineering systems. Engineers can't search through APIs—it's not meant for that.

I think that the story evolution of Cortex also helped align our go-to-market team around that narrative.

What is your main day-to-day job as CEO? Who are your direct reports?

My direct reports are basically our executive team—the VP staff. We now have an executive leading pretty much every part of the organization, so everyone—from a VP of Engineering to a VP of Sales, a VP of Customer Experience, and a VP of Finance—has their own team that reports to them.

Co-Founders Anish Dhar and Ganesh Datta with Cortex team.

I also do a bunch of skip-level meetings. I think that's really important. The company is just about 100 people, so I still know everyone in the company. We're remote-first, even though we try to have a lot of in-person sessions. So Slack is super critical to our day-to-day, and I just stay plugged into all the Slack channels and read all the updates and everything.

Tell us about how raising money has played out so far?

Our most recent round of funding was our Series C, which we raised about six months ago. We raised $60 million. But going all the way back to five years ago, we were part of the Y Combinator Winter 2020 batch. Y Combinator was a huge part of our story and really helped shape the company into what it is today.

Coming out of Y Combinator, we raised our seed round with Sequoia—a $2.5 million seed round. Then they and Tiger Global led our Series A about a year and a half later. We raised our Series B with IVP about a year after the Series A.

I would say that fundraising—I hate to take it back to storytelling, but that's essentially what it is. You build really important relationships with a lot of different venture firms along the way. Certain firms really resonate with the story and certain ones don't, and you find that out super quickly. I think we've been really lucky in that everyone who's invested in the company really believes in this idea that IDPs, which is the name of our market, will be very similar to what on-call or APM is—where every engineering leader will buy an IDP in the same way they buy these tools, just because you need that to get visibility into the quality of your engineering team. I think that's been really great.

But every round has been a challenge. For some companies, especially those 10x-ing year over year, like many AI startups, fundraising can feel as simple as snapping your fingers and getting 10 term sheets.

But if you’re not one of those hyper-growth companies—which is most of us—you really have to figure things out. You start with a grand vision, but with each funding round, the pitch shifts: from selling the vision alone to backing it with data. By Series C, the numbers should tell the story more than the narrative. That’s a big change even from Series A, which is still heavy on storytelling. It’s something founders need to keep in mind.

Source: Cortex.

I think we've been lucky in that the market and the timing have generally been in our favor to help share the data as well. But every chapter requires you to rethink things. For my Series D, we started Cortex at a time when AI wasn't the top-of-mind thing for everyone in the world. The reality is that if you look at the funding rounds that happen today, they're all AI-focused. And rightfully so—this is the biggest paradigm shift, the biggest technological shift we've seen in a long time since cloud. So how does that impact my story? How does that impact our go-to-market? It has to. I'd be stupid not to think about that and how to incorporate that in. I think you just have to be aware of what's going on in the environment and how you adapt and put yourself in a position of strength.

What benefits do you get from going through Y Combinator?

I’ll share some things that are great and some things that kind of suck, too, because I think it’s important to talk about both.

What’s great about YC is the instant brand recognition. They’re the number one startup accelerator by brand and thought leadership, and that helps a ton with hiring. Our first founding engineer actually found us through the YC portal, reached out, and he’s still with us today—he’s been instrumental to our success. That wouldn’t have happened without YC. Same with our first few customers. |

Early on, you’re selling them on a dream and a pretty shitty product, and the YC brand gave us credibility and trust we wouldn’t have had otherwise. The other big thing is accountability. Our batch had 350 companies, but we were split into groups of about 12, and every two weeks, we had to answer: what did you accomplish, what revenue did you close, what did you learn? That forcing function was really valuable.

Source: Y Combinator.

What’s not so great is that the advice can be generic. With so many companies, it’s hard for them to give you very specific guidance. As a dev tools company, a lot of it didn’t apply, and honestly, we ignored a bunch of it. Halfway through, for example, our group partner told us flat out: “You don’t have revenue, you don’t have customers, you’re never going to raise a seed—you should pivot.” Logically, sure, that made sense. But practically, it didn’t. The market didn’t exist yet, and we knew as engineers that this was a real problem. So we just said, “Fuck it, we’re not listening.” That was actually a pivotal moment—trusting ourselves over outside advice. But I can see how another team might’ve taken that advice blindly and gone the wrong way.

How are you using AI in your day-to-day operations?

It's such a powerful tool that has impacted so many areas. Engineering is obvious with coding assistance—the entire engineering team uses Cursor or GitHub Copilot. It's not like some companies claim a 10x increase in productivity. That's definitely not happening in most companies, but it has improved productivity and automated many boilerplate tasks engineers have to do, like writing tests. So from that perspective, I think it's a big win.

AI has also been a huge help for me personally. I’ll often bounce ideas off it—things like messaging or even drafting an email.

ChatGPT is phenomenal at quickly generating solid copy that you can then tweak so it doesn’t read like AI slop. It’s not the finished product, but it’s a great starting point and really powerful for riffing on ideas when you give it the right context. |

Once you feed it your internal docs and company guides, it gets even better—it actually understands how Cortex works, which makes it way more useful.

Marketing uses it all the time for similar messaging and copy reasons—writing blog posts. Sales has been really interesting as well, where we can upload transcripts of calls that we had with customers or prospects and then ask questions and iterate on insights: "What would you have done differently? How would you approach this?"

I think every function has found a utility for it that's been really interesting.

Why build as a remote company?

We never really wanted to do remote, to be honest, but the day after we signed our seed round, COVID happened. So we were kind of forced to build a remote company. Being remote actually helped us in a lot of ways with hiring our early engineering team, because they were living all around the U.S. With COVID and everything, it just made it easier to scale.

Dream team.

That being said, I'm a huge proponent of in-person work. Right now, the company is pretty distributed across the U.S., but we have the majority of the company either in the Bay Area or New York. Last year, we actually opened up a small New York office that allowed people in New York to start coming in. We're probably going to do it in other cities as well. I think it's been a total game-changer. We don't require people to come in, but I think enough people see the benefits where it's just—there are certain things that you need to get in a room, get on a whiteboard, talk it through. Certain conversations happen organically in person.

I think, over time, we probably want to switch to a hybrid model that leans more toward in-person work, but it'll probably happen over a few years.

How do you get the best out of yourself personally and professionally?

Personally, I think it's a few different things. One, I have a really close relationship with my co-founders, and I think that's a very important part of our journey at Cortex, because there's no one who really understands what you're going through like your co-founder. When you're on the same wavelength and can talk about problems across the company and just have really open, honest conversations, it really strengthens the culture and also just makes you a more effective leader because you can give each other feedback and be very open about it. Generally, that's the kind of culture that we've tried to embody in Cortex—to be very open and give feedback when needed.

The other thing is just having a set of founders who might not even be in the same industry, but just in different parts of their journey. It's funny—even founders who have nothing to do with developer tools or engineering or whatever, it's funny how many similar types of problems you go through. Just classes of problems around hiring, culture, and performance, or whatever it is. I think it's important to sometimes have that as a gut check.

Then I think different founders have different views on this, but I was very intentional about the types of people who invested in Cortex and who served on our board. I think I actually have a really good relationship with our board as well, where I can call them and pretty much talk to them about anything around the company. It's a very high degree of trust. I'd say those are the three things that I use.

And that’s it! You can follow and connect with Anish over on LinkedIn and Twitter, and don’t forget to check out Cortex’s website.

BRAIN FOOD 🧠

TOOLS WE RECOMMEND 🛠️

Every week, we highlight tools we like and those we actually use inside our business and give them an honest review. Today, we are highlighting Framer*—the site builder trusted by startups to Fortune 500.

See the full set of tools we use inside of Athyna & Open Source CEO here.

HOW I CAN HELP 🥳

P.S. Want to work together?

Hiring global talent: If you’re hiring tech, business or ops talent and want to do it 80% less, check out my startup, Athyna. 🌏

See my tech stack: Find our suite of tools & resources for both this newsletter and Athyna here. 🧰

Reach an audience of tech leaders: Advertise with us if you want to get in front of founders, investors and leaders in tech. 👀

|

Reply